DCP-LA, a New Strategy for Alzheimer's Disease Therapy

Tomoyuki Nishizaki*

Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is characterized by extensive deposition of amyloid β (Aβ) and formation of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) consisting of hyperphosphorylated Tau. So far, a variety of AD drugs targeting Aβ have been developed, but ended in failure. A recent focus on AD therapy, therefore, is development of Tau-targeted drugs. Aβ activates glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β), that plays a central role in Tau phosphorylation, responsible for NFT formation. The linoleic acid derivative DCP-LA has been developed as a promising drug for AD therapy. DCP-LA serves as a selective activator of PKCε and a potent inhibitor of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B). DCP-LA restrains Tau phosphorylation efficiently due to PKCε-mediated direct inactivation of GSK-3β, to PKCε/Akt-mediated inactivation of GSK-3β, and to receptor tyrosine kinase/insulin receptor substrate 1/phosphoinositide 3-kinase/3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1/Akt-mediated inactivation of GSK-3β in association with PTP1B inhibition. Moreover, DCP-LA ameliorates spatial learning and memory impairment in 5xFAD transgenic mice, an animal model of AD. Consequently, combination of PKCβ activation and PTP1B inhibition must be an innovative strategy for AD therapy.

Introduction

Accumulating evidence has pointed to the role of amyloid β (Aβ), a main body of amyloid (senile) plaques, and Tau protein, a main body of neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs), in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Huge studies have been done for development of AD drug targeting Aβ, but no expecting drug has been obtained. Recent target, therefore, has been turned to Tau.

Tau is abundantly expressed in neurons of the central nervous system and stabilizes microtubules by interacting with tubulin. Microtubules are the tracks for motor proteins bearing intracellular transport of vesicles, organelles and protein complexes1,2, and Tau modulates microtubule dynamics including axonal transport3-6. Tau is upregulated during neuronal development, to promote generation of cell processes and establish cell polarity7.

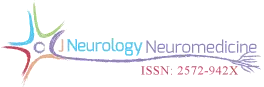

When hyperphosphorylated, Tau detaches from the microtubules and forms fibrils in an insoluble form, referred to as paired helical filaments (PHFs), and NFTs comprises aggregation of PHFs8,9. Tau is phosphorylated by a variety of serine/threonine protein kinases such as glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β), cyclin-dependent kinase 5 (Cdk5)/p25, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 (ERK2), S6 kinase (S6K), microtubule affinity-regulating kinase (MARK), SAD kinase (SADK), protein kinase A (PKA), calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) or Src family kinases such as Fyn and c-Abl (Figure 1)10-14.

Figure 1: Protein kinases relevant to Tau phosphorylation. The proline-directed kinases GSK-3β, Cdk5/p25, ERK2, and S6K and the non-proline-directed kinases MARK, SADK, PKA, and CaMKII phosphorylate Tau at the Ser/Thr residues. The non-receptor tyrosine kinases Fyn and c-Alb phosphorylate Tau at the tyrosine residues.

Tau from the AD brain is phosphorylated at eleven Ser/Thr-Pro and nine Ser/Thr-X sites. Proline-directed kinases such as GSK-3β, Cdk5/p25, ERK2, and S6K phosphorylate Tau at Thr181, Ser202/T205, Thr212/S214, Thr231/Ser235, and Ser396/Ser404 on Ser-Pro or Thr-Pro motifs in the regions flanking the repeat domains10-12. Non-proline-directed kinases such as MARK, SADK, PKA, and CaMKII phosphorylate Tau at Ser262, Ser 320, Ser324, and Ser356 on KXGS motifs in the repeat domains (R1-R4)11,13,14. Fyn and c-Abl, on the other hand, phosphorylate Tau at Tyr-18 and Tyr-39411.

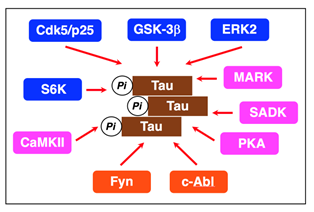

GSK-3β is abundantly expressed in the brain, preferentially in the hippocampus. GSK-3β acts as the main executioner of Tau phosphorylation in PHFs15,16. Intriguingly, GSK-3 accelerates the rate of Tau phosphorylation several-fold, if Tau is pre-phosphorylated by priming kinases such as non-proline-directed kinases17-19. Of Tau phosphorylation sites, Ser396 phosphorylation is a key step in the PHF formation20. Once a priming kinase phosphorylates Tau at Ser404, GSK-3β phosphorylates Tau at Ser400, followed by sequential phosphorylation of Ser396 (Figure 2)20. GSK-3β, alternatively, phosphorylates Tau at Ser202 directly, but Thr231 phosphorylation requires for Ser235 pre-phosphorylation20.

Figure 2: GSK-3β plays a critical role in PHF-Tau phosphorylation. Tau is initially phosphorylated by priming kinases such as non-proline-directed kinases (non-PDK). When GSK-3β activation is enhanced by Aβ, GSK-3β accelerates Tau-Ser396 phosphorylation, responsible for PHFs and NFTs, causing AD.

Interaction between Aβ and GSK-3β

GSK-3β is originally in the active form. When phosphorylated at Ser9, GSK-3β is inactivated, but when phosphorylated at Tyr216, GSK-3β activation is enhanced21.

Aβ activates the non-receptor tyrosine kinase Fyn, to phosphorylate and activates GSK-3β, leading to somatodendritic accumulation of phosphorylated Tau22. Aβ1-42 phosphorylates GSK-3β at Tyr216 and promotes Tau phosphorylation in PC-12 cells23. Aβ, alternatively, activates GSK-3β by decreasing serine phosphorylation as a result of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibition/inactivation24. Chronic exposure of Aβ downregulates Akt phosphorylation, to activate GSK-3β and increase Tau phosphorylation25. Soluble Aβ oligomers inhibit insulin signaling relevant to Akt activation, to activate GSK-3β and increase Tau phosphorylation26. Intracellular Aβ1-42 promotes Tau phosphorylation and induces neuronal loss27. GSK-3β exacerbates Aβ-induced neurotoxicity and cell death28.

Amyloid precursor protein (APP) intracellular domain (AICD), that is produced from γ-secretase-mediated APP cleavage, activates GSK-3β29 or enters the nucleus and activates gene transcription, increasing the GSK-3β mRNA and protein30. C-terminal fragments of APP stimulate GSK-3β activation, to increase Tau phosphorylation and induce apoptosis31.

Regulation of GSK-3β and Tau phosphorylation

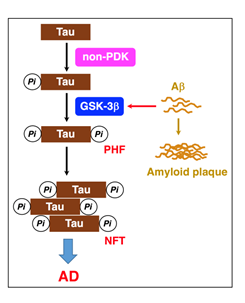

The serine/threonine protein kinases such as PKCε32, Akt32, PKA33, integrin-linked kinase (ILK)34, Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII)35, p90 ribosomal protein S6 kinase (p90RSK)36, and protein kinase C-related kinase 2 (Prk2)37 inactivate GSK-3β by directly phosphorylating at Ser9 (Figure 3). Pyk238, that binds to SH2 and SH3 domain-containing proteins like Src kinases, and Fyn22 activate GSK-3β by phosphorylating at Tyr216 directly (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Inactivation and activation of GSK-3β.PKCε, Akt, PKA, ILK, CaMKII, p90RSK, and Prk2 phosphorylate GSK-3β at Ser9 and inactivate GSK-3β. Pyk2 and Fyn phosphorylate GSK-3β at Tyr216 and activate GSK-3β.

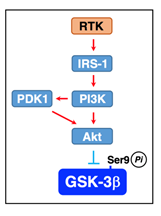

Akt1 is activated by being phosphorylated at Thr308 and Ser473 through the major pathway along a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK)/insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS-1)/PI3K/3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1 (PDK1)/Akt axis32. Then, Akt inactivates GSK-3β by phosphorylating at Ser9 and restrains Tau phosphoryaltion32. In the brain, insulin or insulin-like growth-factor 1(IGF1) binds to and activates the RTK insulin receptor involving GSK-3β inactivation.

Figure 4: RTK-mediated GSK-3β inactivation. Akt is activated through a pathway along a RTK/IRS-1/PI3K/PDK1/Akt axis and inactivate GSK-3β by phosphorylating at Ser9.

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is also shown to phosphorylate and inactivate GSK-3β39. Aβ1-42 upregulates expression of adenylate kinase-1 (AK1), to inhibit AMPK, thereby leading to GSK-3β activation and Tau phosphorylation40. A contradictory finding is that AMPK by itself phosphorylates Tau at Ser262 and induces tauopathy41. Moreover, a specific agonist of sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 (S1PR1) linked to Gi protein reduces Tau-Ser262 phosphorylation in rat hippocampal slices42. This effect may be caused by AMPKα inactivation due to protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) activation through a pathway along an S1PR1/Gi protein/(Cdc42/Rac1)/Pak1/PP2A axis.

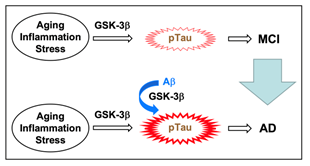

Aging, inflammation, and stress activate GSK-3β, which triggers Tau phosphorylation, responsible for mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a preliminary group of AD (Figure 5). Aβ further activates GSK-3β and accelerates Tau phosphorylation, leading to progression into AD from MCI (Figure 5)43,44. Aggregation of hyperphosphorylated Tau causes tauopathies, a class of neurodegenerative diseases, that include frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17, progressive supranuclear palsy, Pick's disease, and corticobasal degeneration as well as AD. Agents that have the potential to suppress GSK-3β activation, thus, could become beneficial preventive and therapeutic drugs for AD.

Figure 5: GSK-3β is a key factor for MCI and AD. Aging, inflammation, and stress activate GSK-3β and phosphorylate Tau, causing MCI. Aβ enhances GSK-3β activation and accelerates Tau phosphorylation, leading to progression into AD from MCI.

Tau-targeting drugs

Aβ and Tau serve as an initiator and an executor of AD, respectively45. Current AD therapeutic approaches focus upon targeting Tau pathologies. A variety of Tau-targeting drugs have been developed as follows: i) Hsp90 inhibitors such as geldanamycin, radicicol, and 17AAG, that degrade and dispose of hyperphosphorylated Tau46, ii) Inhibitors of Aβ-induced Tau phosphorylation such as kamikihito, DHA, and curcumin47,48, iii) Tau aggregation inhibitors such as methylthioninium chloride and leucomethylthioninium, iv) O-GlcNAcase inhibitors49. Tau is subjected to O-GlcNAc transferase-mediated O-GlcNAcylation at the Ser/Thr residues, that is the same sites as phosphorylation, and O-GlcNAcase neutralizes Tau O-GlcNAcylation. O-GlcNAcase inhibitors, therefore, promote Tau O-GlcNAcylation, thereby preventing Tau phosphorylation and aggregation50, v) GSK-3β inhibitors such as pyrazine, the flavonoid morin, MMBO, the thiadiazolidinone derivative NP-12, and the traditional Chinese herbal medicine Angelica sinensis51-55, vi) mTOR inhibitors56,57. Aβ activates mTOR, followed by activation of S6K, that phosphorylates Tau at Ser262, Ser214, and Thr21212. mTOR inhibitors, therefore, could prevent Tau phosphorylation, vii) Inhibitors of Tau fibrillization such as phenothiazine, the cyanine dye N744, polyphenol, porphyrin, anthracyclines, phenylthiazolyl-hydrazide, rhodanine, and aminothienopyridazine58,59, and viii) microtubule stabilizing agents including natural products such as taxanes, epothilones, discodermolide, dictyostatin, eleutherobin, sarcodyctins, laulimalide, peloruside A, cyclostreptin, taccalonolides, zampanolide, dactylolide, ceratamines, dicumarol, jatrophanes, tubercidin, lutein, and davunetide, and synthetic agents such as GS-164, estradiol analogues, 5HPP-33, triazolopyrimidines, phenylpyrimidines, pyridopyridazines, pyridotriazines, and pyridazines60-62. Successful results in the AD therapy, however, have not been obtained with any drugs as yet.

8-[2-(2-Pentyl-cyclopropylmethyl)-cyclopropyl]-octanoic acid (DCP- LA)

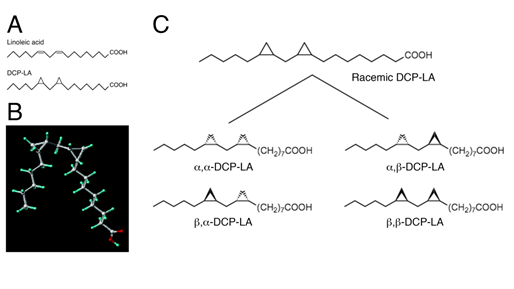

Several lines of evidence have pointed to the role of cis-unsaturated free fatty acids (uFFAs) such as arachidonic, linoleic, linolenic, oleic, and docosahexaenoic acid in cognitive functions63-71. Then, one would think that uFFAs might be available as an anti-dementia drug. uFFAs, however, are promptly metabolized and decomposed before arriving in the brain, even though orally or intravenously taken into the body. To address this issue, we have synthesized the linoleic acid derivative DCP-LA with cyclopropane rings instead of cis-double bonds, that exhibits stable bioactivities (Figure 6 A,B)72.

DCP-LA induces a long-lasting facilitation of hippocampal synaptic transmission by enhancing presynaptic α7 ACh receptor responses to stimulate glutamate release under the control of PKCε72-75. In addition, DCP-LA activates CaMKII due to inhibition of protein phosphatase 1 (PP1), to enhance postsynaptic AMPA receptor responses and facilitate hippocampal synaptic transmission76.

The facilitatory action of DCP-LA on hippocampal synaptic transmission accounts for improvement of Aβ,sub>1-40

- and mutant Aβ-induced spatial learning deficits in rats77,78, scopolamine-induced spatial learning and memory disorders in rats77, spatial learning and memory deterioration in senescence accelerated mice 8 (SAMP8)79,80, and spatial learning and memory impairment in 5xFAD transgenic mice, an animal model of AD32.

PKC is classified into the conventional PKC isozymes α, βI, βII, and γ, the novel PKC isozymes δ, ε, η, and θ, the atypical PKC isozymes α/&gamm a; and ζ, and the PKC-like isozymes μ and ν. All the PKCs have the phosphatidylserine (PS) binding site and are activated by diacylglycerol (DG). Much interestingly, DCP-LA is capable of selectively activating PKCε in a Ca2+- and DG-independent manner81. DCP-LA binds to the PS binding/associating sites Arg50 and Ile89 in the C2-like domain of PKCε, which are distinct from the DG binding site in the C1 domain, at the carboxyl-terminal end and the cyclopropane rings, respectively82.

Racemic DCP-LA contains possible 4 diastereomers such as α,-, α,β-, β,α-, and β,-DCP-LA (Figure 6C). To develop DCP-LA as a medical drug, each diastereomer was separated and each characteristic was examined. Of 4 diastereomers α,β-DCP-LA activates PKCε selectively and stimulates presynaptic release of glutamate, dopamine, and serotonin, with the highest potency83.Of great interest is that DCP-PA serves as not only a selective PKCε activator but a potent inhibitor of protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B). DCP-LA inhibits PTP1B by its direct interaction84.

Figure 6: Structure of DCP-LA. DCP-LA has cyclopropane rings instead of cis-double bonds on linoleic acid (A,B). Racemic DCP-LA contains possible 4 diastereomers such as α,-, α,β-, β,α-, and β,β-DCP-LA (C).

DCP-LA efficiently inactivates GSK-3β and restrains Tau phosphorylation by cooperation of PKCε activation and PTP1B inhibition

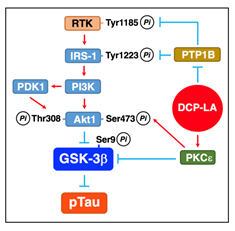

PKCε, activated by DCP-LA, inactivates GSK-3β by directly phosphorylating at Ser9 (Figure 6)32. Activated PKCε, alternatively, activates Akt by directly phosphorylating at the serine residue, followed by inactivation of GSK-3β (Figure 6)32.

When activated, RTK phosphorylates its own receptor at Tyr1185 and activates IRS-1 by phosphorylating at Tyr1222. Activated IRS-1 recruits and activates PI3K, which produces phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-triphosphate (PIP3) by phosphorylating phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2). PIP3 binds to and activates PDK1. PI3K and/or PDK1 activate Akt by phosphorylating at the serine and threonine residues. RTK and IRS-1 are inactivated through PTP1B-mediated tyrosine dephosphorylation. DCP-LA-induced PTP1B inhibition, therefore, represses inactivation of RTK and IRS-1, allowing Akt activation through a RTK/IRS-1/PI3K/PDK1/Akt pathway, to phosphorylate and inactivate GSK-3β (Figure 6)32.

PKCε activation or PTP1B inhibition, thus, has the potential to restrain Tau phosphorylation by inactivating GSK-3β each independently. Cooperation of PKCε activation and PTP1B inhibition, however, could inactivate GSK-3β and restrain Tau phosphorylation more efficiently than each solitary treatment32. In experiments using PC-12 cells, PKCε overexpression and PTP1B deficiency activate Akt and inactivate GSK-3β synergistically32. Aβ1-42 activates GSK-3β by reducing Ser9 phosphorylation and increases Tau phosphorylation at Ser202/Thr205 and Ser396, and the effects of Aβ1-42 are clearly neutralized by DCP-LA32.

5xFAD mice are widely used as an animal model of AD. 5xFAD mice are APP/presenilin 1 (PS1) double transgenic mice that coexpress five familial forms of AD mutations such as the Swedish/London/Florida mutations and the M146L/L286V mutations85. The Aβ1-42 levels in the 5xFAD mouse brain is shown to increase in an age-dependent manner and spatial memory deficits are found from 4-5 months of age85. The significantly higher levels of GSK-3β-Ser9 phosphorylation is also found in the hippocampus of 5xFAD mice from 4-5 months of age as compared with the levels for wild-type control mice, indicating that the GSK-3β activity is enhanced in 5xFAD mice, possibly in association with Aβ1-42 increase86. Moreover, a greater deal of Tau-Ser396 phosphorylation, responsible for PHF formation, is found in the hippocampus of 5xFAD mice86. DCP-LA suppresses GSK-3β activation and reduces Tau-Ser396 phosphorylation in the hippocampus of 5xFAD mice to an extent similar to that for wild-type control mice32. DCP-LA, thus, enables efficient suppression of Tau-Ser396 hyperphosphorylation by activating PKCε and inhibiting PTP1B simultaneously.

DCP-LA ameliorates spatial learning and memory decline in 5xFAD mice, that occurs in parallel with GSK-β activation and an increase in Tau phosphorylation, but such effect is not obtained with galanthamine, that is clinically used for treatment of mild to moderate AD32. In addition, DCP-LA improves Aβ1-40- and mutant Aβ-induced spatial learning deficits in rats77,78, scopolamine-induced spatial learning and memory disorders in rats77, spatial learning and memory deterioration in senescence accelerated mice79,80. DCP-LA-induced improvement of cognitive decline is not due to only inhibition of GSK-β and restraint of Tau phosphorylation. Facilitation of synaptic transmission in alive neurons would be required for improvement of cognitive decline. DCP-LA has the potential to facilitate hippocampal synaptic transmission by enhancing presynaptic α7 ACh receptor responses under the control of PKCε72-75 and postsynaptic AMPA receptor responses under the control of CaMKII in association with PP1 inhibition76. This action of DCP-LA is also a strong advantage as an AD therapeutic drug as compared with Tau-targeted drugs including GSK-β inhibitors. Tau-targeted drugs proposed possess no direct facilitatory action on synaptic transmission, and therefore, early improvement of cognitive decline would not be expected by those drugs.

A beneficial effect on 5xFAD mice is obtained with oral administration of DCP-LA at a dose of 1 mg/kg body weight, corresponding to ~3 μM. This dose, in the light of the fact that the optimal concentration of DCP-LA in the in vitro experiments is 100 nM, seems to be appropriate and possible for clinical use. Overall, DCP-LA may shed a beam of hope on AD prevention and treatment.

Figure 7: DCP-LA-induced suppression of Tau phosphorylation. PKCε, activated by DCP-LA, inactivates GSK-3β by phosphorylating Ser9 directly or through a PKCε/Akt pathway, to restrain Tau phosphorylation (pTau). DCP-LA-induced PTP1B inhibition, alternatively, activates Akt through a RTK/IRS-1/PI3K/PDK1/Akt pathway by repressing tyrosine dephosphorylation of RTK and IRS-1, followed by Ser9 phosphorylation and inactivation of GSK-3β, to restrain Tau phosphorylation.

Conclusion

Tau-targeted drugs for AD therapy under development include i) Hsp90 inhibitors, ii) inhibitors of Aβ-induced Tau phosphorylation, iii) Tau aggregation inhibitors, iv) O-GlcNAcase inhibitors, v) GSK-3β inhibitors, vi) mTOR inhibitors, vii) inhibitors of Tau fibrillization, and viii) microtubule stabilizing agents. The mechanism underlying the inhibitory effect of DCP-LA on Tau phosphorylation is distinct from that for any drugs provided until now. DCP-LA restrains Tau phosphorylation efficiently due to PKCε-mediated direct inactivation of GSK-3β, to PKCβ/Akt-mediated inactivation of GSK-3β, and to RTK/IRS-1/PI3K/PDK1/Akt-mediated inactivation of GSK-3β in association with PTP1B inhibition. Consequently, combination of PKCε activation and PTP1B inhibition must be an innovative strategy for AD therapy.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interests.

References

- Hirokawa N, Takemura R. Molecular motors and mechanisms of directional transport in neurons. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005; 6(3): 201-214.

- Mandelkow E, von Bergen M, Biernat J, et al. Structural principles of tau and the paired helical filaments of Alzheimer's disease. Brain Pathol. 2007; 17(1): 83-90.

- Garcia ML, Cleveland DW. Going new places using an old MAP: tau, microtubules and human neurodegenerative disease. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001; 13(1): 41-48.

- Binder LI, Guillozet-Bongaarts AL, Garcia-Sierra F, et al. Tau, tangles, and Alzheimer's disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005; 1739(2-3): 216-223.

- Cuchillo-Ibanez I, Seereeram A, Byers HL, et al. Phosphorylation of tau regulates its axonal transport by controlling its binding to kinesin. FASEB J. 2008; 22(9): 3186-3195.

- Trinczek B, Ebneth A, Mandelkow EM, et al. Tau regulates the attachment/detachment but not the speed of motors in microtubule-dependent transport of single vesicles and organelles. J Cell Sci. 1999; 112(Pt 14): 2355-2367.

- Drubin DG, Kirschner MW. Tau protein function in living cells. J Cell Biol. 1986; 103(6 Pt 2): 2739-2746.

- Grundke-Iqbal I, Iqbal K, Tung YC, et al. Abnormal phosphorylation of the microtubule-associated protein τ (tau) in Alzheimer cytoskeletal pathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986; 83(13): 4913-4917.

- Brion JP, Couck AM, Passareiro E, et al. Neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer's disease: an immunohistochemical study. J Submicrosc Cytol. 1985; 17(1): 89-96.

- Patrick GN, Zukerberg L, Nikolic M, et al. Conversion of p35 to p25 deregulates Cdk5 activity and promotes neurodegeneration. Nature. 1999; 402(6762): 615-622.

- Jeganathan S, Hascher A, Chinnathambi S, et al. Proline-directed pseudo-phosphorylation at AT8 and PHF1 epitopes induces a compaction of the paperclip folding of Tau and generates a pathological (MC-1) conformation. J Biol Chem. 2008; 283(46): 32066-32076.

- Pei JJ, Björkdahl C, Zhang H, et al. p70 S6 kinase and tau in Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2008; 14(4): 385-392.

- Ren QG, Wang YJ, Gong WG, et al. Escitalopram ameliorates Tau hyperphosphorylation and spatial memory deficits induced by protein kinase A activation in Sprague Dawley rats. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015; 47(1): 61-71.

- Yamamoto H, Yamauchi E, Taniguchi H, et al. Phosphorylation of microtubule-associated protein tau by Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in its tubulin binding sites. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002; 408(2): 255-262.

- Hernandez F, Lucasa JJ, Avila J. GSK3 and tau: two convergence points in Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013; 33 Suppl 1: S141-144.

- Imahori K. The biochemical study on the etiology of Alzheimer's disease. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B Phys Biol Sci. 2010; 86(1): 54-61.

- Singh TJ, Haque N, Grundke-Iqbal I, et al. Rapid Alzheimer-like phosphorylation of tau by the synergistic actions of non-proline-dependent protein kinases and GSK-3. FEBS Lett. 1995; 358(3): 267-272.

- Cohen P, Frame S. The renaissance of GSK3. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2001; 2(10): 769-776.

- Beurel E, Grieco SF, Jope RS. Glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3): regulation, actions, and diseases. Pharmacol Ther. 2015; 148: 114-131.

- Li T, Paudel HK. Glycogen synthase kinase 3β phosphorylates Alzheimer's disease-specific Ser396 of microtubule-associated protein tau by a sequential mechanism. Biochemistry. 2006; 45(10): 3125-3133.

- Forde JE, Dale TC. Glycogen synthase kinase 3: a key regulator of cellular fate. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007; 64(15): 1930-1944.

- Li C, Götz J. Somatodendritic accumulation of Tau in Alzheimer's disease is promoted by Fyn-mediated local protein translation. EMBO J. 2017; pii: e201797724.

- Hu M, Waring JF, Gopalakrishnan M, et al. Role of GSK-3β activation and α7 nAChRs in Aβ1-42-induced tau phosphorylation in PC12 cells. J Neurochem, 2008; 106(3): 1371-1377.

- Takashima A. GSK-3β and memory formation. Front Mol Neurosci. 2012; 5: 47.

- Abbott JJ, Howlett DR, Francis PT, et al. Aβ1-42 modulation of Akt phosphorylation via α7 nAChR and NMDA receptors. Neurobiol Aging. 2008; 29(7): 992-1001.

- Tokutake T, Kasuga K, Yajima R, et al. Hyperphosphorylation of Tau induced by naturally secreted amyloid-β at nanomolar concentrations is modulated by insulin-dependent Akt-GSK3β signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2012; 287(42): 35222-35233.

- Rebeck GW, Hoe HS, Moussa CE. β-Amyloid1-42 gene transfer model exhibits intraneuronal amyloid, gliosis, tau phosphorylation, and neuronal loss. J Biol Chem. 2010; 285(10): 7440-7446.

- Takashima A, Noguchi K, Sato K, et al. Tau protein kinase I is essential for amyloid β protein-induced neurotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993; 90(16): 7789-7793.

- Ryan KA, Pimplikar SW. Activation of GSK-3 and phosphorylation of CRMP2 in transgenic mice expressing APP intracellular domain. J Cell Biol. 2005; 171(2): 327-335.

- Balaraman Y, Limaye AR, Levey AI, et al. Glycogen synthase kinase 3β and Alzheimer's disease: pathophysiological and therapeutic significance. Cell Mol Life Sci 2006; 63(11): 1226-1235.

- Kim HS, Kim EM, Lee JP, et al. C-terminal fragments of amyloid precursor protein exert neurotoxicity by inducing glycogen synthase kinase-3β expression. FASEB J. 2003; 17(13): 1951-1953.

- Kanno T, Tsuchiya A, Tanaka A, et al. Combination of PKCε activation and PTP1B inhibition effectively suppresses Aβ-induced GSK-3β activation and Tau phosphorylation. Mol Neurobiol. 2016; 53(7): 4787-4797.

- Shelly M, Lim BK, Cancedda L, et al. Local and long-range reciprocal regulation of cAMP and cGMP in axon/dendrite formation. Science. 2010; 327(5965): 547-552.

- Naska S, Park KJ, Hannigan GE, et al. An essential role for the integrin-linked kinase-glycogen synthase kinase-3β pathway during dendrite initiation and growth. J Neurosci. 2006; 26(51): 13344-13356.

- Song B, Lai B, Zheng Z, et al. Inhibitory phosphorylation of GSK-3 by CaMKII couples depolarization to neuronal survival. J Biol Chem. 2010; 285(52): 41122-41134.

- Valerio A, Ghisi V, Dossena M, et al. Leptin increases axonal growth cone size in developing mouse cortical neurons by convergent signals inactivating glycogen synthase kinase-3β. J Biol Chem. 2006; 281(18): 12950-12958.

- Zhao Z, Wang Z, Gu Y, et al. Regulate axon branching by the cyclic GMP pathway via inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3 in dorsal root ganglion sensory neurons. J Neurosci. 2009; 29(5): 1350-1360.

- Sayas CL, Ariaens A, Ponsioen B, et al. GSK-3 is activated by the tyrosine kinase Pyk2 during LPA1-mediated neurite retraction. Mol Biol Cell. 2006; 17(4): 1834-1844.

- Song JS, Kim EK, Choi YW, et al. Hepatocyte-protective effect of nectandrin B, a nutmeg lignan, against oxidative stress: Role of Nrf2 activation through ERK phosphorylation and AMPK-dependent inhibition of GSK-3β. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2016; 307: 138-149.

- Park H, Kam TI, Kim Y, et al. Neuropathogenic role of adenylate kinase-1 in Aβ-mediated tau phosphorylation via AMPK and GSK3β. Hum Mol Genet. 2012; 21(12): 2725-2737.

- Galasso A, Cameron CS, Frenguelli BG, et al. An AMPK-dependent regulatory pathway in tau-mediated toxicity. Biol Open. 2017; pii: bio.022863.

- St-Cyr Giguère F, Attiori Essis S, Chagniel L, et al. The sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 1 agonist SEW2871 reduces Tau-Ser262 phosphorylation in rat hippocampal slices. Brain Res. 2017; 1658: 51-59.

- Ballatore C, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ. Tau-mediated neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007; 8(9): 663-672.

- Hurtado DE, Molina-Porcel L, Iba M, et al. Aβ accelerates the spatiotemporal progression of tau pathology and augments tau amyloidosis in an Alzheimer mouse model. Am J Pathol. 2010; 177(4): 1977-1988.

- Stancu IC, Ris L, Vasconcelos B, et al. Tauopathy contributes to synaptic and cognitive deficits in a murine model for Alzheimer's disease. FASEB J. 2014; 28(?): 2620-2631.

- Opattova A, Filipcik P, Cente M, et al. Intracellular degradation of misfolded tau protein induced by geldanamycin is associated with activation of proteasome. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013; 33(2): 339-348.

- Watari H, Shimada Y, Tohda C. New treatment for Alzheimer's disease, kamikihito, reverses amyloid-β-induced progression of tau phosphorylation and axonal atrophy. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014; 2014: 706487.

- Ma QL, Yang F, Rosario ER, et al. β-amyloid oligomers induce phosphorylation of tau and inactivation of insulin receptor substrate via c-Jun N-terminal kinase signaling: suppression by omega-3 fatty acids and curcumin. J Neurosci. 2009; 29(28): 9078-9089.

- Wischik CM, Harrington CR, Storey JM. Tau-aggregation inhibitor therapy for Alzheimer's disease. Biochem Pharmacol. 2014; 88(4): 529-539.

- Graham DL, Gray AJ, Joyce JA, et al. Increased O-GlcNAcylation reduces pathological tau without affecting its normal phosphorylation in a mouse model of tauopathy. Neuropharmacology. 2014; 79: 307-313.

- Berg S, Bergh M, Hellberg S, et al. Discovery of novel potent and highly selective glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK3β) inhibitors for Alzheimer's disease: design, synthesis, and characterization of pyrazines. J Med Chem. 2012; 55(21): 9107-9119.

- Gong EJ, Park HR, Kim ME, et al. Morin attenuates tau hyperphosphorylation by inhibiting GSK3β. Neurobiol Dis. 2011; 44(2): 223-230.

- Onishi T, Iwashita H, Uno Y, et al. A novel glycogen synthase kinase-3 inhibitor 2-methyl-5-(3-{4-[(S)-methylsulfinyl]phenyl}-1-benzofuran-5-yl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole decreases tau phosphorylation and ameliorates cognitive deficits in a transgenic model of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurochem. 2011; 119(6): 1330-1340.

- Serenó L, Coma M, Rodríguez M, et al. A novel GSK-3β inhibitor reduces Alzheimer's pathology and rescues neuronal loss in vivo. Neurobiol Dis. 2009; 35(3): 359-367.

- Zhang Z, Zhao R, Qi J, et al. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3β by Angelica sinensis extract decreases β-amyloid-induced neurotoxicity and tau phosphorylation in cultured cortical neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2011; 89(3): 437-447.

- Caccamo A, Magrì A, Medina DX, et al. mTOR regulates tau phosphorylation and degradation: implications for Alzheimer's disease and other tauopathies. Aging Cell. 2013; 12(3): 370-380.

- Caccamo A, Majumder S, Richardson A, et al. Molecular interplay between mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), amyloid-β, and Tau: effects on cognitive impairments. J Biol Chem. 2010; 285(17): 13107-13120.

- Ballatore C, Brunden KR, Piscitelli F, et al. Discovery of brain-penetrant, orally bioavailable aminothienopyridazine inhibitors of tau aggregation. J Med Chem. 2010; 53(9): 3739-3747.

- Ballatore C, Brunden KR, Huryn DM, et al. Microtubule stabilizing agents as potential treatment for Alzheimer's disease and related neurodegenerative tauopathies. J Med Chem. 2012; 55(21): 8979-8996.

- Brunden KR, Ballatore C, Lee VM, et al. Brain-penetrant microtubule-stabilizing compounds as potential therapeutic agents for tauopathies. Biochem Soc Trans. 2012; 40(4): 661-666.

- Zhang B, Carroll J, Trojanowski JQ, et al. The microtubule-stabilizing agent, epothilone D, reduces axonal dysfunction, neurotoxicity, cognitive deficits, and Alzheimer-like pathology in an interventional study with aged tau transgenic mice. J Neurosci. 2012; 32(11): 3601-3611.

- Brunden KR, Yao Y, Potuzak JS, et al. The characterization of microtubule-stabilizing drugs as possible therapeutic agents for Alzheimer's disease and related tauopathies. Pharmacol Res. 2011; 63(4): 341-351.

- Ikeuchi Y, Nishizaki T, Matsuoka T, et al. Arachidonic acid potentiates ACh receptor currents by protein kinase C activation but not by receptor phosphorylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996; 221(3): 716-721.

- Nishizaki T, Matsuoka T, Nomura T, et al. Modulation of ACh receptor currents by arachidonic acid. Mol Brain Res. 1998; 57(1): 173-179.

- Nishizaki T, Nomura T, Matsuoka T, et al. Arachidonic acid as a messenger for the expression of long-term potentiation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999; 254(2): 446-449.

- Nishizaki T, Matsuoka T, Nomura T, et al. Arachidonic acid potentiates currents through Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors by interacting with a CaMKII pathway. Mol Brain Res. 1999; 67(1): 184-189.

- Nishizaki T, Nomura T, Matsuoka T, et al. Arachidonic acid induces a long-lasting facilitation of hippocampal synaptic transmission by modulating PKC activity and nicotinic ACh receptors. Mol Brain Res. 1999; 69(2): 263-272.

- Nishizaki T, Ikeuchi Y, Matsuoka T, et al. Short-term depression and long-term enhancement of ACh-gated channel currents induced by linoleic and linolenic acid. Brain Res. 1997; 751(2): 253-258.

- Nomura T, Nishizaki T, Enomoto T, et al. A long-lasting facilitation of hippocampal neurotransmission via a phospholipase A2 signaling pathway. Life Sci. 2001; 68(25): 2885-2891.

- Nishizaki T, Ikeuchi Y, Matsuoka T, et al. Oleic acid enhances ACh receptor currents by activation of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II. Neuroreport. 1997; 8(3): 597-601.

- Yaguchi T, Yamamoto S, Nagata T, et al. Effects of cis-unsaturated free fatty acids on PKC-ε activation and nicotinic ACh receptor responses. Mol Brain Res. 2005; 133(2): 320-324.

- Tanaka A, Nishizaki T. The newly synthesized linoleic acid derivative FR236924 induces a long-lasting facilitation of hippocampal neurotransmission by targeting nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2003; 13(6): 1037-1040.

- Yamamoto S, Kanno T, Nagata T, et al. The linoleic acid derivative FR236924 facilitates hippocampal synaptic transmission by enhancing activity of presynaptic α7 acetylcholine receptors on the glutamatergic terminals. Neuroscience. 2005; 130(1): 207-213.

- Kanno T, Tanaka A, Nishizaki T. Linoleic acid derivative DCP-LA stimulates vesicular transport of α7 ACh receptors towards surface membrane. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2012; 30(1): 75-82.

- Kanno T, Tsuchiya A, Tanaka A, et al. The linoleic acid derivative DCP-LA increases membrane surface localization of the ε7 ACh receptor in a protein 4.1N-dependent manner. Biochem J. 2013; 450(2): 303-309.

- Kanno T, Yaguchi T, Nagata T, et al. DCP-LA stimulates AMPA receptor exocytosis through CaMKII activation due to PP-1 inhibition. J Cell Physiol. 2009; 221(1): 183-188.

- Nagata T, Yamamoto S, Yaguchi T, et al. The newly synthesized linoleic acid derivative DCP-LA ameliorates memory deficits in animal models treated with amyloid-β peptide and scopolamine. Psychogeriatrics. 2005; 5(4): 122-126.

- Nagata T, Tomiyama T, Mori H, et al. DCP-LA neutralizes mutant amyloid β peptide-induced impairment of long-term potentiation and spatial learning. Behav Brain Res. 2010; 206(1): 151-154.

- Yaguchi T, Nagata T, Mukasa T, et al. Linoleic acid derivative DCP-LA improves learning impairment in SAMP8. Neuroreport. 2006; 17(1): 105-108.

- Kanno T, Yaguchi T, Shimizu T, et al. 8-[2-(2-Pentyl-cyclopropylmethyl)-cyclopropyl]-octanoic acid and its diastereomers improve age-related cognitive deterioration. Lipids. 2012; 47(7): 687-695.

- Kanno, T. Yamamoto H, Yaguchi T, et al. The linoleic acid derivative DCP-LA selectively activates PKC-ε, possibly binding to the phosphatidylserine binding site. J Lipid Res. 2006; 47(6): 1146-1156.

- Kanno T, Tsuchiya A, Shimizu T, et al. DCP-LA activates cytosolic PKCε by interacting with the phosphatidylserine binding/associating sites Arg50 and Ile89 in the C2-like domain. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2015; 37(1): 193-200.

- Shimizu T, Kanno T, Tanaka A, et al. α,-DCP-LA selectively activates PKC-ε and stimulates neurotransmitter release with the highest potency among 4 diastereomers. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2011; 27(2): 149-158.

- Tsuchiya A, Kanno T, Nagaya H, et al. PTP1B inhibition causes Rac1 activation by enhancing receptor tyrosine kinase signaling. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2014; 33(4): 1097-1106.

- Oakley H, Cole SL, Logan S, et al. Intraneuronal β-amyloid aggregates, neurodegeneration, and neuron loss in transgenic mice with five familial Alzheimer's disease mutations: potential factors in amyloid plaque formation. J Neurosci. 2006; 26(40): 10129-40.

- Kanno T, Tsuchiya A, Nishizaki T. Hyperphosphorylation of Tau at Ser396 occurs in the much earlier stage than appearance of learning and memory disorders in 5XFAD mice. Behav Brain Res. 2014; 274: 302-306.